As was the norm for a midweek night, the joint was anything but jumping. Three guys were chatting and passing the chutney to and fro at the table right behind me, while I perched awkwardly on a too-tall bar stool and snapped a courtesy poppadom, waiting for my order to be boxed and bagged up. How did we kill time before we all had phones for moments like this? Glance around at this and that, I suppose. Soak up the vibe. The pile of plastic-coated menus the size of pulpit bibles on the corner of the counter? Logged. The spike for cheques next to the battleship-grey NCR till? Duly registered. That’s the visible covered; what about the audible? As a regular, I was well practised at tuning out the piped adult-oriented raga, so the murmur of conversation from the table behind me had all my attention. The topic seemed to be music in general and heavy metal in particular. One of the voices stood out, though, triggering a full-on multiple-synapse memory alarm. American, definitely, and that tell-tale nagging, drawling, raspy whine was ... no, it can’t be. No way. I span [spun? - Ed.] slowly and uneasily on my stool, oh so casually, to check out my ridiculous hunch.

Bob Dylan was picking at his biriani, sitting opposite Dave “Trotsky Beard” Stewart and a younger guy. I remembered how the Eurythmic was said to have converted an old church just around the corner into a recording studio, so the surrealism of the moment was offset by a certain logic. As for the other guy? No idea. The tape op, maybe?

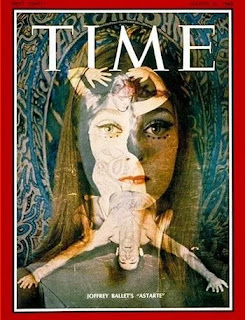

In my peripheral vision - it’s rude to stare - I clocked with approval that Bob Dylan was cosplaying Eighties Dylan to perfection: the cloud of auburn curls, the black leather jacket, the messy white muslin scarf. The two on the other side of the table leaned forward a couple of inches. The Prophet had a point to make.

“Heavy metal? They grow out of it. It’s just a phaaaase.” (You did the voice in your head as you were reading that, right?)

“Your order, sir.” What? Oh, yes, sorry. I paid and left, swinging my steaming plastic bag like a priest with his smoking censer. Don’t look back. Bob Dylan Live at the Local Tandoori. Tangled up in ghee.

Rewind about a decade. Recently arrived in London, I was living the life: holed up alone in a tiny Earls Court bedsit with rising damp and an uncooperative gas meter, chain-listening to Bob Dylan. I owned all the albums up to and including the newly released Street Legal - even Self Portrait, more fool me. And that night the man himself would be performing at the exhibition centre across the road for the first time in the UK since the “Judas” tour, ’twas-in-another-lifetime ago. I’d managed to scrape together the cash to bag tickets for every gig, six nights straight, with just enough left over for the Blackbushe bash with Clapton & Co. later that summer.

It was a religious experience. A foretaste of the Rapture. Even though the acoustics were dreadful (no surprise for a concrete hangar built to house motor shows), even though all the gigs were practically carbon copies of the first night, even though that Scarlett woman’s Stuka screech of a violin was a regrettable error of artistic judgement, even though the setlist bafflingly eschewed “Visions of Johanna”, and even though our hero’s interaction with the audience was limited to announcing the interval by repeating night after night, word for word, “We’ll be right back; I gotta make a telephone call,” who cares? It’s Bob Dylan, crysake. He didn’t need to talk to us, because his art spoke to us – it spoke for us.

Since then, it’s been downhill all the way for Bob and me. For our relationship, I mean. Our thing. I made it as far as Slow Train Coming before I found myself listening to each of his new releases in full before I was ready to decide whether to splash out on buying the thing. Without my noticing, a new Dylan album had become just an album, like any other album by any other artist, to be judged on its actual merits rather than as an article of faith. And those merits proved to be ever fewer and far-betweener as the years rolled by.

Fast-forward to 1999. Well, whaddya know? Bob Dylan was coming to play a show in my adopted hometown in Spain, and a friend who worked for the promoters got me guest-listed up. Was I thrilled? Not exactly. Would I have gone if I’d had to queue up and pay for the tickets? Maybe, for old time’s sake, but maybe not.

Little had changed in the twenty-year interim since the last time I’d seen him, at Blackbushe, and nothing had changed for the better. Having left the leather-’n’-muslin look behind not long before, he was now decked out like a Lithuanian production designer’s idea of what an Albuquerque undertaker might look like. The sound was even worse than Earls Court, the arrangements were generic mid-tempo background Americana, the vocals were a monotonous drone with a weird upspeaky note tacked onto the end of every line, making most of the songs unrecognisable (Play “Visions of Joanna”, Bob! He already did, pal), and he didn’t say a word all evening - not even a paltry mumbled thank you to acknowledge the inexplicable applause, let alone any kind of cute telephone-call spiel to connect with the kids. It was, no question about it, the most disgraceful, fuck-you live performance by a major artist I’ve ever attended - and, yes, I’ve seen Van Morrison. The last vestiges of my once-burning faith were being tested to the limit.

Five years or so later, Chronicles: Volume One was published, to be met, inevitably, with awed critical acclaim. That’s when the long-creaking-under-the-strain levee finally broke for me. This was partly because when I read the book I was irked no end by the apparent lack of any copyediting whatsoever - “He’s a poet; don’t you dare change a comma,” I assume the internal meeting must have gone - but what finally made me turn my back on the holy cause was Bob Dylan’s cheatin’ heart. His prose was found to be pebbledashed with phrases he’d stolen, like a sugar-rushing jackdaw, from an improbably diverse variety of original sources. He not only heisted Hemingway, mugged Mark Twain and hijacked Jack London, but he also filched and pilfered at will from Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu potboilers. He even saw fit to describe someone’s desk by lifting, practically word for word, a lengthy description he’d found in an encyclopedia of desks cleverly titled An Encyclopedia of Desks.

His paintings follow the same metatextual, ahem, approach to repurposing, ahem, creative content. For every Cartier-Bresson photograph he’s daubed in oils, supposedly depicting a scene from his own “travels in Asia”, you can find some backpacker’s holiday snap that he’s purloined from Pinterest and painted over, just because he can.

Keen to squeeze every last bit of potential from his M.O., he even blagged chunks of text about Moby-Dick from some SparkNotes website when he was forced to give a Nobel Prize (!) acceptance speech. You know, as one does. Well, maybe as one does if one is a teenager with an unwritten assignment to hand in tomorrow.

Dylan with Dave van Ronk, 1962. The photographer's focus tells the whole story

Bob Dylan is a fraudster, a phony, a charlatan, a conman, a grifter, an empty vessel, a plagiarist on an industrial scale and a lazy-ass liar. Like the proverbial asylum inmate, he’s the self-identified Napoleon, in rags or dressed to the nines. He’s both the joker and the thief.

But so what? That’s not the point. He’s Dylan - in italics, like Che is Che or Mother Teresa (another chancer) is Mother Teresa. He moves in mysterious ways, his blunders to perform. And, anyway, isn’t it all about the form, not the content? The how, not the what?

Let’s review the evidence.

Lyrically, even at his peak (generally accepted as having been his mid-’60s three-album run from Bringing It All Back Home to Blonde on Blonde, with Blood on the Tracks as a tardy afterthought) he was little more than a run-of-the-mill post-beatnik who riffed on random snippets of sub-Symbolist imagery for shits and giggles. A poundshop Rimbaud or a budget Baudelaire. Do you view life or loss or truth or justice or love or - cough - theft any differently because of the insights you’ve gained from a Bob Dylan lyric? Me neither. (If you actually do, congratulations; the comments they are a-waitin’.) He can turn a tidy phrase from time to time, I’ll grant you, but, shit, so can Tim Rice.

Musically, he’s a klutzy joke, as cackhanded as Lou Reed or any Sex Pistol. (For hilarious proof of this, watch the YouTube videos of his attempts to master his part during the recording session for “We Are The World”, as even Quincy Jones goes down with an acute case of the awes in the Holy Presence, finding himself incapable of uttering the all-too-obvious words: “Just get your goddamn act together, man.”)

Instrumentally, even on a good day he’s a bedroom guitar player, with a sense of metric structure so wayward that in live performance, with no producer on hand to have a discreet word, you’re as likely to get a middle seven or a middle nine as a middle eight. His melodies are unremarkable and mostly forgettable, his chord changes are hackneyed and predictable, and his whole approach to songwriting is derivative at best and out-and-out thievery at worst. (If you think I’m overstating my case, check out Paul Clayton’s “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons?” and you won’t think twice again, alright?)

Vocally, he’s certainly got a characteristic timbre - no argument there - but so does, say, Tom Waits, yet try to imagine Tom Waits pitching an album of old Sinatra songs or Yuletide ditties to his record company.

So how the hell has Bob Dylan, after six decades and despite all the shameless chicanery and musical mediocrity outlined above, managed to retain his bulletproof status as Dylan? What’s with the enduring hagiography? It’s simple. He hit lucky. He was plucked from the pack in the early-’60s folk boom to be the one who’d receive the juiciest recording contract and the concomitant PR hard sell. It could have been Dave van Ronk we’re revering to this day and chucking all the Pulitzers and Nobels at (if he’d lived), but it happened to be Bob Dylan who drew the golden ticket. It wasn’t long before everybody who was anybody was covering “Blowin’ in the Wind”, so he rode the zeitgeist to the max - as we certainly didn’t say then - and then he dug in his spurs and rode on as the movement formerly known as protest morphed into hippiedom and beyond.

Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Jackson Browne, Tom Waits, Bruce Springsteen ... a good few singer-songwriters are just as deserving as Bob Dylan of being anointed as The One, but they all emerged too late. The king had already been crowned and he wasn’t about to abdicate his throne.

Bob Dylan was, and for many people apparently still is, the poster boy with nothing of any particular note to say for those with nothing of any particular note to think or feel. He encouraged his reputation as the enigmatic and unfathomable genius because there was precious little there to fathom. But for the once-faithful members of the flock like me to openly admit to that now would be to recognise that we allowed ourselves to be duped like gullible rubes. Nobody forced us. We don’t even have that excuse. We gulped down the tincture in the “Drink Me” bottle of our own volition, swallowing every last drop of that heady, addictive brew, in blissful denial of what had been - or should have been - staring us in the face since about 1964: that the Great Wizard was just a little guy behind a curtain with a panel full of knobs and levers, which he’s still pushing and pulling sixty years down the line. Hey, wouldn’t you, if the shtick still works?

I’m out. I scaled the perimeter fence and abandoned the compound. Now I feel much the same way I imagine an ex-Moonie or a renegade Scientologist must feel. So, how does it feel? Well, it’s a bit embarrassing to confess that I once tumbled so willingly, heavily and unsuspectingly into the embrace of the ultimate long con, but, hey, we all make mistakes. Mostly it feels great. Liberating. A burden lifted. I heartily recommend it. You shall be released.

Archie Valparaiso is Master Of Quoits on the games deck of luxury cruise liner The Hastings Banda, proud flagship of prestigious Cruise Bargains n' Containers™ line. Why has it taken him two furshlugginer years to ink screed for th' IoF©? "My role as Master of Quoits is both demanding and rewarding, leaving little time for yarn-spinning, and anyway fuck you," he yelled yesterday from Number Three Hold.